What is the fastest animal on Earth? The answer might surprise you—it’s not the cheetah. While the cheetah dominates on land, the animal kingdom’s true speed champion soars through the sky at breathtaking velocities that make terrestrial sprinters look slow in comparison.

From diving peregrine falcons exceeding 240 mph to sprinting cheetahs and lightning-fast marine predators, nature has engineered remarkable speed machines across every habitat.

Table of Contents

The Science Behind Animal Speed

Speed in the animal kingdom isn’t just about raw power—it’s a complex combination of biology, physics, and evolutionary adaptation. Understanding what makes animals fast helps us appreciate these natural marvels.

How Speed Is Measured in Animals

Scientists use various techniques to accurately measure animal speeds. High-speed cameras capture frame-by-frame movement, while GPS tracking collars monitor velocity over extended periods. Radar guns provide real-time speed data during pursuits.

For diving birds, researchers factor in gravity-assisted acceleration. Marine animals require underwater tracking technology that accounts for water resistance. Land animals are often measured using calibrated vehicles following alongside.

The challenge lies in ensuring animals are exerting maximum effort. A cheetah casually trotting differs vastly from one chasing prey at full sprint.

Factors That Influence Maximum Velocity

Body size plays a crucial role in determining speed potential. Medium-sized animals occupy a “sweet spot” where muscle power and body mass optimize for maximum velocity. Too small, and muscle contraction limits speed; too large, and mass creates excessive drag.

Muscle composition matters tremendously. Fast-twitch muscle fibers enable explosive acceleration and high-speed bursts. Animals built for speed possess higher proportions of these specialized fibers.

Environmental factors also impact performance. Terrain type, wind conditions, temperature, and elevation all affect how fast an animal can move. Open plains favor sprinters, while forests require agility over pure speed.

Evolution’s Role in Speed Development

Speed evolved as both a hunting tool and survival mechanism. Predators developed faster sprints to catch prey, while prey animals countered with their own speed adaptations—an evolutionary arms race spanning millions of years.

Natural selection favored individuals with speed-enhancing traits. Cheetahs with more flexible spines caught more food and survived to reproduce. Slower individuals faced starvation or became prey themselves.

This pressure created specialized body structures: streamlined shapes reducing drag, longer limbs increasing stride length, and powerful cardiovascular systems delivering oxygen to muscles during intense exertion.

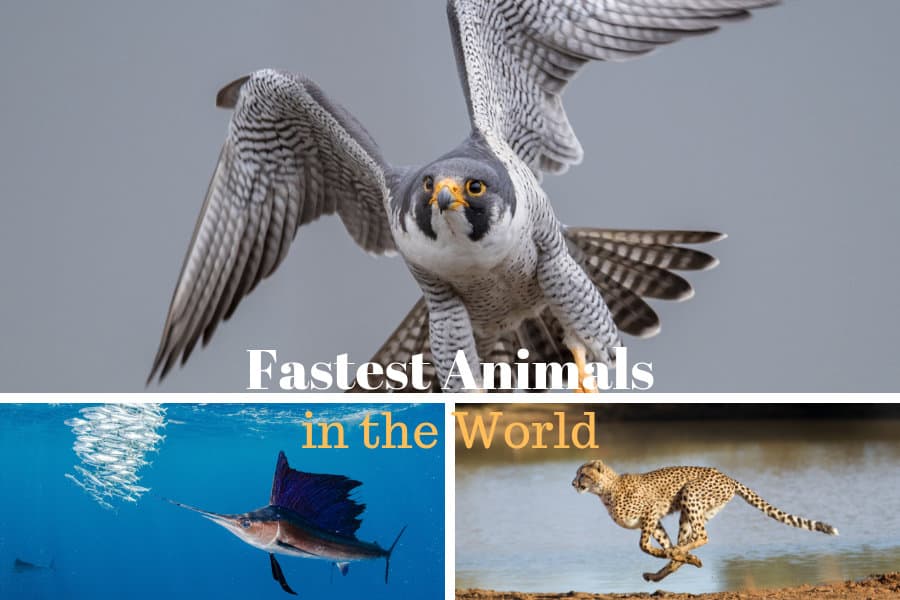

The Fastest Animal on Earth: Peregrine Falcon

The peregrine falcon claims the undisputed title of fastest animal on Earth. During hunting dives called stoops, these magnificent birds reach speeds exceeding 240 mph (389 km/h), making them nature’s ultimate speed champion.

Record-Breaking Diving Speeds

Peregrine falcons achieve their incredible velocity through gravity-assisted dives from great heights. They spot prey from above, then tuck their wings and plummet at breathtaking speeds that would tear apart less-specialized creatures.

The fastest recorded peregrine falcon dive reached 242 mph, though some scientists estimate they may hit 350 mph under ideal conditions. This speed is more than three times faster than any land animal.

During these stoops, the impact force can kill prey mid-flight. The falcon closes its talons into a fist, striking with devastating precision. Their exceptional eyesight locks onto targets from incredible distances.

Anatomical Adaptations for Extreme Speed

Peregrine falcons possess unique physical features enabling their record speeds. Their pointed wings create a streamlined airfoil effect, minimizing drag during dives. Stiff, narrow feathers further reduce air resistance.

Large keel bones anchor powerful flight muscles. These muscles can flap wings up to four times per second, providing explosive acceleration. The birds’ heart rate reaches 600-900 beats per minute during flight.

Special structures called tubercles inside their nostrils regulate airflow. This innovation allows peregrines to breathe even at extreme velocities where air pressure would otherwise damage their respiratory system.

Their vision processing speed is the fastest of any tested animal. This lets them track and adjust to prey movements during high-speed pursuits with incredible precision.

Global Distribution and Hunting Behavior

Peregrine falcons inhabit every continent except Antarctica. They adapt to diverse environments from coastal cliffs to urban skyscrapers, where tall buildings substitute for natural nesting sites.

These birds prefer hunting smaller flying species: pigeons, songbirds, small waterfowl, and bats. They scan for prey while cruising at moderate speeds around 40-60 mph, then execute their famous stoop when targets appear.

Peregrines mate for life but quickly replace deceased partners. They return to the same nesting sites (eyries) annually, laying 3-4 eggs each breeding season.

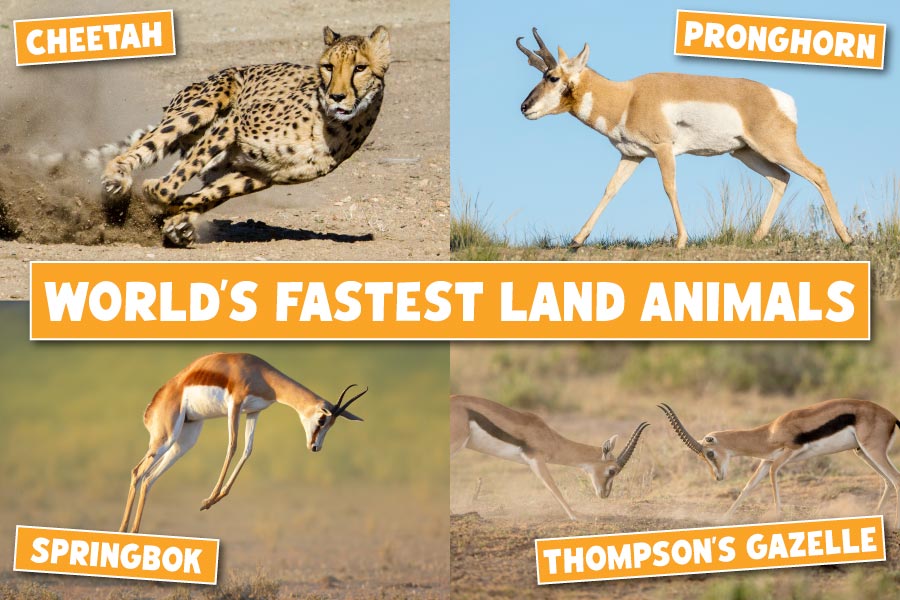

Fastest Land Animals: Speed Demons of the Savanna

Land animals face different challenges than flying or swimming creatures. Gravity, friction, and terrain create obstacles that make terrestrial speed even more impressive.

Cheetah: The Undisputed Land Speed Champion

The cheetah holds the crown as the fastest land animal on Earth, sprinting at speeds up to 70 mph (120 km/h). These magnificent cats can accelerate from 0 to 60 mph in just three seconds—faster than most sports cars.

Cheetahs evolved specifically for speed over short distances. Their slender, aerodynamic bodies minimize drag while running. A remarkably flexible spine extends and compresses with each stride, increasing step length dramatically.

Long, muscular legs provide power and reach. Non-retractable claws grip the ground like track spikes. Large nasal passages intake maximum oxygen during sprints. The cheetah’s tail acts as a rudder, providing balance during sharp turns at high speed.

Black tear marks below their eyes reduce sun glare, maintaining visual focus on prey during chases. Their lightweight bone structure and small head keep mass low for optimal speed.

However, cheetahs sacrifice endurance for velocity. They can maintain top speed for only 200-300 meters before overheating forces them to stop. This makes hunting a high-stakes game—success or starvation.

Pronghorn Antelope: The Endurance Runner

The pronghorn antelope ranks second among land animals with speeds reaching 60 mph (98 km/h). More impressively, they sustain 45 mph for several miles—an endurance feat no cheetah can match.

Native to North American grasslands, pronghorns evolved in response to now-extinct predators that required both speed and stamina to escape. Their oversized heart and lungs circulate oxygen efficiently during extended chases.

Hollow hair provides insulation while reducing body weight. Cushioned hooves absorb impact shock during high-speed running across varied terrain. Their wide field of vision spots predators from great distances across open plains.

Pronghorns represent the fastest long-distance runners in the animal kingdom, demonstrating that speed and endurance can coexist in a single species.

Springbok: Africa’s Speed and Agility Master

Springboks reach speeds of 55 mph (88 km/h) while demonstrating remarkable agility through their characteristic “pronking” behavior. These spectacular leaps can reach 11 feet in height.

Scientists theorize pronking serves multiple purposes: raising alarms to alert herd members, confusing predators with unpredictable movements, and demonstrating fitness to potential mates.

Their tan and white coat blends perfectly with South African grasslands, providing camouflage. Springboks combine speed with exceptional jumping ability, making them difficult targets for predators.

Other Notable Fast Land Animals

The quarter horse reaches 55 mph in short sprints, making it among the fastest domesticated animals. Bred specifically for quarter-mile races, they showcase explosive acceleration.

Blue wildebeest clock 50 mph during their famous migrations across African plains. Lions, often portrayed as slow, actually sprint at 50 mph during short hunting bursts—fast enough to catch many prey species.

African wild dogs sustain 44 mph for extended periods while hunting in coordinated packs. Greyhounds hit 45 mph, making them the fastest dog breed. The ostrich, despite being flightless, runs 45 mph on powerful two-legged strides.

Fastest Marine Animals: Speed Beneath the Waves

Ocean environments present unique challenges and opportunities for speed. Water resistance requires different adaptations than air or land.

Sailfish: Ocean’s Speed Champion

The sailfish claims the title of fastest fish and fastest marine animal, slicing through water at speeds up to 68 mph (110 km/h). Their torpedo-shaped bodies minimize drag while their powerful tails generate thrust.

The distinctive sail-like dorsal fin can be raised or lowered to regulate body temperature and reduce turbulence. During high-speed pursuits, they keep it folded to maximize streamlining.

Sailfish hunt in groups, using their speed to herd schools of smaller fish into tight balls before attacking. Their long, sharp bills stun prey with rapid side-to-side slashes.

Black Marlin: Powerful Ocean Sprinter

Black marlins reach speeds around 80 mph (130 km/h) according to some estimates, though exact measurements remain challenging. These massive fish can weigh over 1,500 pounds while maintaining impressive velocity.

Their streamlined bodies and crescent-shaped tails propel them through water with remarkable efficiency. Black marlins are apex predators, using speed to overtake fast-swimming prey like tuna and mackerel.

Like sailfish, marlins possess bills used for stunning prey. Their size and power make them formidable ocean hunters capable of sustained high-speed chases.

Dolphins and Other Fast Swimmers

Dolphins reach speeds of 37 mph using streamlined bodies and powerful tail flukes. They harness their speed for hunting, escaping predators, and social interaction through playful racing.

Leatherback sea turtles, despite their bulk, swim at 22 mph—impressive for reptiles. Orcas hit 34 mph when hunting, using teamwork and intelligence alongside speed to capture prey.

Fastest Flying Animals: Masters of the Sky

Beyond the peregrine falcon, numerous bird species demonstrate extraordinary flight speeds through different techniques and habitats.

Golden Eagle: The Silver Medalist

Golden eagles dive at speeds exceeding 200 mph (320 km/h), making them the second-fastest animals on Earth. These powerful raptors are larger than peregrine falcons, with wingspans reaching 7 feet.

They hunt medium-sized mammals and birds, using their diving speed to strike with lethal force. Golden eagles inhabit mountainous regions across the Northern Hemisphere, nesting on cliff faces and tall trees.

White-Throated Needletail: Horizontal Flight Champion

The white-throated needletail potentially flies faster than any bird in level flight, with estimated speeds exceeding 105 mph (170 km/h). However, these speeds remain officially unverified.

This large swift migrates across enormous distances between Asia and Oceania. Its narrow tail and streamlined body enable exceptional horizontal flight speed without gravity assistance.

Frigatebird: The Oceanic Speedster

Frigatebirds cruise at 95 mph during sustained flight over ocean waters. Their enormous wingspan relative to body weight allows efficient long-distance flight. They can stay airborne for weeks during migration.

These birds possess the remarkable ability to fly against airflow, actively pushing through headwinds. This adaptation enables them to maintain speed in challenging conditions.

Spur-Winged Goose: Fastest Waterfowl

The spur-winged goose reaches 88 mph, making it the fastest flying waterfowl species. They rarely use maximum speed for hunting, instead relying on it for predator evasion and long-distance migration.

These large geese inhabit African wetlands, grazing on vegetation near water bodies. Their powerful flight muscles enable both speed and endurance during seasonal movements.

Common Swift and Other Quick Fliers

The common swift flies at 69 mph during normal flight—faster than a cheetah runs on land. These birds spend most of their lives airborne, even sleeping while flying.

Gyrfalcons reach 90 mph during level flight, making them formidable Arctic hunters. Eurasian hobbies hit 100 mph, specializing in catching other birds mid-flight through superior speed and agility.

Relative Speed: Size Matters

When measuring speed relative to body size, different animals emerge as champions. This metric reveals fascinating insights about movement efficiency.

The Paratarsotomus Macropalpis Mite

The Southern Californian mite Paratarsotomus macropalpis is the fastest organism on Earth relative to body size. Moving at 322 body lengths per second, this tiny creature achieves speeds equivalent to humans running 1,300 mph.

While its absolute speed is just 0.5 mph, the mite’s relative velocity demonstrates incredible muscle efficiency. If humans could match this ratio, we’d achieve supersonic speeds.

Tiger Beetles and Relative Speed Champions

Australian tiger beetles move at 171 body lengths per second, previously holding the relative speed record. These insects are fast absolute runners too, reaching speeds that make them effective predators.

Even the mighty cheetah only achieves 16 body lengths per second despite its 70 mph top speed. This comparison shows how body size fundamentally affects speed measurements.

Speed Adaptations Across Habitats

Different environments require specialized adaptations for achieving maximum speed. Animals evolved unique solutions based on their habitats.

Adaptations for Speed on Land

Land animals need powerful leg muscles and skeletal structures optimized for running. Four-legged animals generally outpace bipeds due to more contact points with the ground.

Flexible spines in cats allow greater stride extension. Hoofed animals benefit from reduced surface area contact, minimizing friction. Long limbs increase step length without requiring faster leg movement.

Adaptations for Speed in Water

Marine animals require streamlined, torpedo-shaped bodies to reduce drag. Powerful tails generate thrust efficiently through water. Some fish like marlins have reduced scale coverage to minimize surface friction.

Dolphins and whales use their horizontal tail flukes differently than fish with vertical tails. This adaptation provides unique propulsion advantages in different swimming styles.

Adaptations for Speed in Air

Flying animals minimize weight through hollow bones and efficient respiratory systems. Pointed wings reduce drag during high-speed flight. Streamlined feathers prevent turbulence.

Large keels anchor powerful flight muscles. One-way airflow through lungs maximizes oxygen intake during sustained flight. High metabolic rates fuel the energy demands of rapid wing movement.

Speed in Hunting and Survival

Speed serves dual purposes in nature: catching food and avoiding becoming food. This creates evolutionary pressure in both predators and prey.

Predators Using Speed for Hunting

Cheetahs rely entirely on speed to catch prey like gazelles and impalas. Their hunting strategy involves stalking within striking distance before unleashing their explosive sprint.

Peregrine falcons use diving speed to generate impact force that kills prey instantly. Their precision strikes eliminate struggles that could allow escape.

African wild dogs use sustained speed combined with pack coordination. They chase prey for miles, taking turns at the front to maintain pressure until the target exhausts.

Prey Using Speed for Escape

Pronghorns evolved extreme speed and endurance to escape predators that no longer exist. This evolutionary legacy makes them “overbuilt” for modern threats.

Gazelles employ zigzag running patterns at high speed, combining velocity with agility to shake pursuing predators. Their acceleration and direction changes challenge even cheetahs.

Fish like tuna use burst speed to escape marine predators. Schooling behavior coordinates group movements that confuse attackers through simultaneous directional changes.

Comparing Speed to Humans

Human speed capabilities pale compared to most animals on this list, yet humans evolved different strengths that ensured survival.

Usain Bolt and Human Speed Records

Usain Bolt achieved a peak speed of 27.8 mph during his world record 100-meter sprint in 2009. This makes him the fastest human ever recorded.

However, this speed wouldn’t earn humans a spot among the top 30 fastest land mammals. Lions, ranking tenth on land animal lists, run 50 mph—nearly twice Bolt’s maximum.

The average human sprinting speed hovers around 15 mph. This seems slow until we consider human evolutionary advantages.

Human Endurance vs. Animal Sprint Speed

Humans evolved as exceptional endurance runners rather than sprinters. Our ability to sweat efficiently, combined with upright posture and long limbs, makes us tireless pursuit hunters.

Ancient humans hunted by tracking prey over many miles until animals collapsed from exhaustion. No cheetah can match human sustained running over marathon distances.

This trade-off between speed and endurance represents different evolutionary strategies. Humans sacrificed sprint speed for stamina and versatility.

Conservation Status of Fast Animals

Many of the world’s fastest animals face serious conservation challenges. Habitat loss, climate change, and human activity threaten these remarkable species.

Endangered Speed Champions

Cheetahs are listed as vulnerable with populations declining. Only about 7,000 remain in the wild due to habitat fragmentation and human-wildlife conflict.

African wild dogs are endangered with fewer than 7,000 individuals surviving. They require large territories that increasingly overlap with human settlements.

Conservation Efforts and Success Stories

Peregrine falcons recovered dramatically after DDT pesticide bans. Once endangered, they’re now listed as least concern thanks to captive breeding and reintroduction programs.

Pronghorn populations rebounded through habitat protection and hunting regulations. Conservation initiatives continue protecting migration corridors essential for their long-distance movements.

Fascinating Speed Facts

The animal kingdom contains numerous surprising speed-related facts that challenge common assumptions.

Unexpected Speed Records

The ostrich is the fastest two-legged animal despite being flightless. Their powerful legs generate speeds of 45 mph with strides exceeding 16 feet.

The spiny-tailed iguana is the fastest lizard at 21.7 mph—officially verified by Guinness World Records through laboratory testing.

Male horseflies are the fastest flying insects, reaching estimated speeds of 90 mph. Their speed helps them catch females during mating pursuits.

Speed and Acceleration Comparisons

Cheetahs accelerate faster than most supercars, reaching 60 mph in under three seconds. This explosive acceleration provides crucial hunting advantages.

Peregrine falcons process visual information faster than any other tested animal. This enables split-second adjustments during high-speed dives.

Sailfish can accelerate from stationary to 68 mph in just seconds, generating forces that would injure less-adapted creatures.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

What is the fastest animal on Earth?

The peregrine falcon is the fastest animal on Earth, reaching diving speeds over 240 mph (389 km/h). In level flight, the white-throated needletail may be fastest at 105 mph, though this remains unverified.

What is the fastest land animal in the world?

The cheetah is the fastest land animal, sprinting up to 70 mph (120 km/h). However, they can only maintain top speed for short distances before overheating forces them to stop.

Which animal is faster than a cheetah?

Many animals are faster than cheetahs. Peregrine falcons dive at 240+ mph, golden eagles at 200+ mph, and several swift species exceed cheetah speeds during flight.

What is the fastest marine animal?

The sailfish is considered the fastest marine animal, reaching speeds up to 68 mph (110 km/h). Black marlins also compete for this title with similar speeds.

How do scientists measure animal speed?

Scientists use high-speed cameras, radar guns, GPS tracking collars, and calibrated vehicles to measure animal speeds. Methods vary by habitat and species characteristics.

Can any animal run faster than 100 mph?

No land animal runs faster than 100 mph. The cheetah tops out around 70 mph. Only flying animals achieve speeds exceeding 100 mph.

Why are animals faster than humans?

Animals evolved specialized body structures for speed: four-legged locomotion, fast-twitch muscle fibers, flexible spines, and lightweight frames. Humans evolved for endurance rather than sprint speed.

What is the fastest bird in horizontal flight?

The white-throated needletail potentially flies fastest horizontally at 105 mph, though unverified. The common swift flies at confirmed speeds of 69 mph during level flight.

How long can a cheetah run at top speed?

Cheetahs maintain top speed for only 200-300 meters (approximately 20-30 seconds) before their body temperature rises dangerously high, forcing them to stop and cool down.

Which animal has the best endurance at high speed?

The pronghorn antelope demonstrates the best combination of speed and endurance, sustaining 45 mph for several miles—far exceeding any other land animal’s sustained high-speed running capability.

Conclusion

The question “what is the fastest animal on Earth” reveals the incredible diversity of speed adaptations across nature’s kingdoms. While the peregrine falcon claims the absolute speed record at over 240 mph during diving stoops, each habitat showcases remarkable speed champions adapted to their unique environments.

The cheetah dominates terrestrial speeds at 70 mph despite lasting only seconds at maximum velocity, while the pronghorn antelope demonstrates that endurance can rival pure speed.

Marine environments feature the sailfish racing through water at 68 mph, and numerous bird species demonstrate that flight unlocks the ultimate speed potential.

These speed records represent millions of years of evolutionary refinement, where survival pressures shaped bodies into specialized machines optimized for velocity.